For decades, vaccine researchers have been enchanted and frustrated with the promise of messenger RNA. The tiny snippets of genetic code are essential in telling cells to build proteins, a basic part of human physiology — and key to unleashing the immune system.

But they've been hard to tame, at least until the coronavirus spurred a global race to create a vaccine.

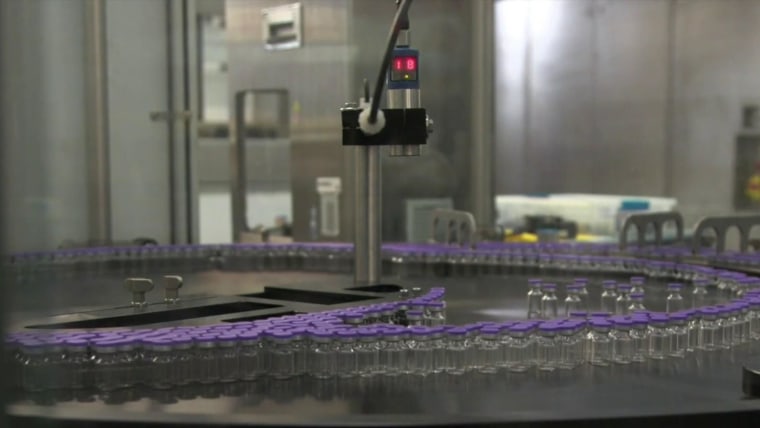

Now, both Pfizer and Moderna are testing their separate vaccine candidates that use messenger RNA, or mRNA, to trigger the immune system to produce protective antibodies without using actual bits of the virus. If the experimental coronavirus vaccines win approval from the Food and Drug Administration, they will be the first-ever authorized vaccines that use mRNA — a development that would not only turn the tide in this pandemic but could also unlock an entirely new line of vaccines against a variety of viruses.

The two experimental vaccines have some key differences that will likely affect who they are administered to and how they are distributed. But experts say promising early results from both camps could be a boon for the technology, which had made progress over nearly three decades but was long thought to be something of a pipe dream.

“This was a brand new platform,” Dr. Carlos del Rio, executive associate dean of the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, said. “There were a lot of people who were skeptical that an mRNA vaccine would work. Scientifically, it makes sense, but there’s no mRNA vaccine out there that has been approved yet.”

Last week, Pfizer released preliminary findings that showed its vaccine candidate is more than 90 percent effective at preventing symptomatic Covid-19. On Monday, Moderna added to the encouraging news, with early results from its Phase 3 trial showing that its experimental vaccine is 94.5 percent effective at preventing the illness. Seeing such consistent results at this stage of the trials is a good sign, del Rio said.

“That makes me feel like, ‘gee, Pfizer wasn’t a fluke,’” he said. “This is for real. This is actually working.”

Though reassuring, the results are still preliminary — the full study results have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal for other scientists to scrutinize — and it’s not yet known how long the vaccines could offer protection, or whether they will perform well across all age groups and ethnicities.

One of the main differences between the two vaccine candidates is how they are stored. Both require two doses, but Pfizer’s vaccine has to be stored at temperatures of minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit or colder, which has raised practicality concerns about how they could be shipped and disseminated. Moderna’s vaccine does not require ultracold storage and can remain stable at regular refrigeration levels — between roughly 36 to 46 degrees Fahrenheit — for 30 days.

This distinction is probably because of how the vaccines’ synthetic mRNA, or messenger RNA, is packaged, according to Paula Cannon, an associate professor of microbiology at the University of Southern California's Keck School of Medicine. On its own, mRNA is a fragile molecule, which means it has to be coated in a protective, fatty covering to keep it stable.

The refrigeration conditions may have to do with how the mRNA was manufactured and stabilized, Cannon said, though those precise details are proprietary to the companies.

Dr. Drew Weissman, a professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, has been an early pioneer in mRNA vaccine research and is now collaborating with BioNTech, a German biotechnology company that has partnered with Pfizer. He said work is ongoing to enhance the experimental vaccine — including improvements to its storage requirements.

“There are definitely improvements that are already being developed,” he said.

Both the Pfizer vaccine and the Moderna vaccine are made using synthetic messenger RNA. Unlike DNA, which carries genetic information for every cell in the human body, messenger RNA directs the body’s protein production in a much more focused way.

“When one particular gene needs to do its work, it makes a copy of itself, which is called messenger RNA,” Cannon said. “If DNA is the big instruction manual for the cell, then messenger RNA is like when you photocopy just one page that you need and take that into your workshop.”

The Pfizer vaccine and the Moderna vaccine use synthetic mRNA that contains information about the coronavirus’s signature spike protein. The vaccines essentially work by sneaking in instructions that direct the body to produce a small amount of the spike protein. Once the immune system detects this protein, the body subsequently begins producing protective antibodies.

“Those antibodies will work not just against the little bit of spike protein that was made following vaccination, but will also recognize and stop the coronavirus from getting into our cells if we’re exposed in the future,” Cannon said. “It’s really a clever trick.”

But as elegant a mechanism as this is in theory, mRNA vaccines have faced real biological challenges since they were first developed in the 1990s. In early animal studies, for instance, the vaccines caused worrisome inflammation.

“That became one of the big questions: How do you get this inside the body without creating an inflammatory response?” said Norman Baylor, president and CEO of Biologics Consulting and the former director of the FDA’s Office of Vaccines Research and Review.

Though neither company has reported any serious safety concerns so far, scientists will continue to monitor participants in both trials over time.

“There’s always a concern when you are trying to trick the immune system — which is what a vaccine does — that you could have unintended side effects,” Cannon said. “The immune system is incredibly complicated and it’s different from person to person.”

The vaccines don’t contain any part of the virus, so recipients can’t become infected from the shots.

“It’s the instructions for just one part of the virus, which by itself can’t do anything,” Cannon said. “It would be like giving somebody a wheel and saying: ‘Here’s a car.’”

Still, mRNA vaccines have never been widely distributed before, which means there will likely be added scrutiny. And while early results from both Pfizer and Moderna have exceeded expectations, some major questions still remain, including how the vaccines perform across different demographics, and how long they are effective, according to Baylor.

“What I’d love to see — and we won’t know this until some time has gone by — is how long this protection lasts,” he said.

If the good results hold up, however, it could open the door to other mRNA vaccines in the near future, Baylor added.

Weissman, whose lab at the University of Pennsylvania demonstrated 15 years ago that mRNA could be used in this way, said that prior to the pandemic, he and his colleagues had been working to launch Phase 1 clinical trials of mRNA vaccines for genital herpes, influenza, HIV and the norovirus.

The technology behind mRNA vaccines is thought to be more versatile than traditional methods of vaccine development, which means they can be manufactured quicker and more economically than others that require using bacteria or yeast to make and purify the coronavirus’s spike protein.

“With an mRNA vaccine, you sit at your computer and design what that piece of RNA is going to look like, and then you have a machine that can make that RNA for you relatively easily,” Cannon said. “In some ways, we’re lucky in 2020 that this very powerful technology was ready for prime time, because it could be a really big advantage.”

"how" - Google News

November 18, 2020 at 05:08AM

https://ift.tt/2IB2y8j

What is mRNA? How Pfizer and Moderna tapped new tech to make coronavirus vaccines - NBC News

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "What is mRNA? How Pfizer and Moderna tapped new tech to make coronavirus vaccines - NBC News"

Post a Comment