Published Feb. 25, 2021

Ann Wallace sat on the couch in her west Houston home on a winter evening in 2015, with her husband, Don, 86, by her side. They had just finished dinner and were ending their day as they had so many others: watching the news and worrying about their son, Don.

Before his first psychotic break at 35, Don had built the kind of life any parent would be proud of. He’d graduated from Texas A&M University with a mechanical engineering degree, married his college sweetheart and had a beautiful baby girl. He was so close with his parents that his father was his best man at his wedding.

But suddenly, Don, their Don, disappeared. He started hearing voices, seeing spies. He believed that people were after him. His parents tried repeatedly to get him help, but in 2014 he went off his medication, threw a rock through a window and took a swing at a police officer. He was committed to Rusk State Hospital three hours north of Houston over his parents’ objections.

They counted the days until his release. Only one more week.

Suddenly, the phone rang.

“There was an assault in the dining hall,” said the caller, a nurse at Rusk. “Don’s unconscious.”

As Don died slowly, his parents repeatedly asked state and hospital officials what had happened to him. But years later, they’re still searching for answers, along with thousands of other Texans. A yearlong Houston Chronicle investigation found that the Wallaces’ son was housed in a secretive system that has suffered for years from underfunding and insufficient oversight.

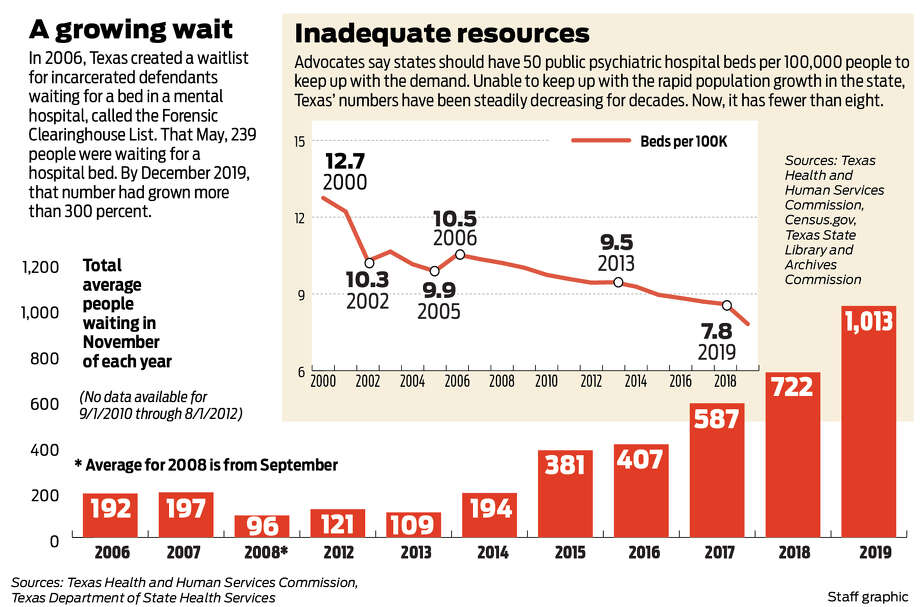

Texas’ mental health system is strained beyond capacity, with waitlists for hospital beds that stretch on for sometimes up to a year. The state’s lack of oversight is so extreme that officials were unable to say which private hospitals received state funds for bed space to help reduce the waitlist. The state just started collecting that information in September.

The state’s 10 public mental hospitals are supposed to be a kind of last safety net for the ill and indigent, but many of them are chaotic and dangerous places, where police visit up to 14 times a day. And that’s for people lucky enough to find a bed.

Budget cuts in the mid-2000s— and a law that streamlined the process of finding someone incompetent to stand trial — left the state unable to keep up with demand for psychiatric hospital beds, creating a shortage that has left some mentally ill people awaiting trial languishing for months in county jails with little support.

While the state has tried to expand its bed space and its funding for community mental health programs, it hasn’t done so fast enough. Some 3.3 million adult Texans — about one in nine adults — suffered from mental illness between 2017 and 2018, the latest data available, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Nearly 840,000 of them reported having unmet needs during that time.

“There’s been serious neglect,” said Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston. “Leadership will say they’ve spent millions of dollars over the last few years and yeah, they have, but it’s too little too late.”

Texas Health and Human Services Commission officials repeatedly denied the Chronicle’s requests for interviews with mental health leaders, including Timothy Bray, association commissioner for state hospital systems, and Dorthy Floyd, former superintendent of Terrell State Hospital who has served as the chairwoman of the Dangerousness Review Board. The board determines if a patient can be moved from a maximum security mental facility to one with minimum security.

“Protecting the health and safety of every person in our direct care, and in the care of a facility we regulate, as well as all staff in these facilities is our top priority,” Christine Mann, a spokeswoman for Texas health and human services, wrote in a prepared statement. “We are grateful Governor Abbott and members of the Texas Legislature have provided additional funding over the past several legislative sessions to help us address the many challenges we face, such as expanding capacity at our state hospitals and securing more beds around the state to better meet the need for care.”

State leaders have been taking steps to try to alleviate strain on the system. They’ve started funding a $2 billion plan to bring an additional 656 beds online across the state mental health system. They’ve allowed for discretion in determining which individuals truly need maximum security mental health care. They’ve even allocated $68 million to address local mental health needs, including jail diversion programs across the state.

Advocates say states should have 50 public psychiatric hospital beds per 100,000 population, but Texas has fewer than 8 per 100,000. The waitlist for a state bed in Texas grew nearly 600 percent from 2012 until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has only exacerbated the shortages.

That means the state has had to rely increasingly on private psychiatric hospitals for beds, which often charge hundreds of dollars more per day than the Medicaid rate.

And as beds remain scarce, there’s less and less room for people seeking help for themselves or are committed by a family member, the Chronicle’s investigation revealed. Roughly 70 percent of the 2,300 beds in the 10 state-run mental hospitals are occupied by people who have been deemed incompetent to stand trial by a court or found not guilty by reason of insanity, records show.

The result is a dangerous and increasingly expensive system that has repeatedly failed to help people such as Wallace, and worse, placed him in danger by housing him with patients with a long history of violent acts, the Chronicle’s investigation found.

TIMELINE: How Texas' mental health system became overwhelmed

From 2014 through 2019, about 100 people died in state hospitals, but details are scant. Texas Health and Human Services Commission officials said not every death is reviewed by a medical committee, but ones involving assaults or questionable deaths would be investigated. The results of those investigations are confidential.

Texas is required to report deaths to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services only if they could be related to restraints or seclusion. State officials reported four deaths during that time period to CMS, but federal officials investigated just one of them, records show.

Don’s death was not reported to federal officials, records show.

A complaint to federal officials can prompt an investigation, but Wallace’s sister, Kathryn, didn’t know she could file one. The state’s investigation was confidential, she was told. The family was given only 13 pages on Don’s death — an ambulance call log from that day, and half a dozen employee logs showing Wallace was punched in the face by another patient.

“It’s useless,” she said.

And so they’ve mourned without closure, wondering how and why Don died, and how many others the system has failed.

Kathryn Preng and her father Don Wallace at Kathryn's home on Sept. 20, 2020, in Houston. Kathryn's brother, also named Don, died as a result of a blow to the head at Rusk State Hospital in 2015. Jimmy Dale Mathis has been charged with murder.

(Mark Mulligan, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)***

Don’s father, also named Don, was a psychologist for the Veteran’s Administration in Houston when his son was young. His only son was healthy, happy, with no hint of mental illness as a child or a teenager, he said. He was a natural on the tennis court. He made friends easily. He got great grades and graduated from Texas A&M, where he met Kathy, a fellow engineering student. They moved to Plano after graduation and got married. Don started a business with Kathy’s help.

In 1993, when Don was 34 years old, they had a baby girl, Julie, four days after Thanksgiving.

Everything seemed to be going according to plan, Kathryn, his older sister, thought.

But the following year, she got a phone call from her brother that made her sink to her knees.

Don was unhinged, spouting off accusations that made no sense.

“My brother has lost his mind,” she thought.

Kathryn is a clinical psychologist, just like her father. At home in Houston, she sat on the floor, staring at the phone clutched tightly in her hands.

Shaking, she dialed her parents, who were vacationing in North Carolina. They had gotten a similar call and already had booked a flight back to Texas.

Kathryn got behind the wheel of her car and headed north to Plano.

She flashed through memories as she drove, searching for a moment that might have warned of Don’s breakdown, but came up with nothing.

A divorce petition filed later that year in Collin County suggests Don’s breakdown had started long before that day.

His wife, Kathy, told the court Don had become emotionally abusive during their six-year marriage; that he tried to drug her with Valium in ice cream; that he had threatened physical abuse.

Don was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, which can cause bouts of paranoia, depression, hallucinations and delusions, soon after Kathryn and her parents arrived. He was hospitalized for the first time that month, at a private facility.

A photo of Don Wallace as a toddler. Don Wallace died as a result of a blow to the head at Rusk State Hospital in 2015. Jimmy Dale Mathis has been charged with murder.

(Mark Mulligan, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)***

Had Don been born a decade or so earlier, he might have been institutionalized at a state-run psychiatric hospital. But in the 1950s, the country went through a mental health reckoning.

News of intolerable conditions at mental hospitals across the U.S. — coupled with the advent of medications such as Thorazine that made commitment unnecessary for some — brought on a new wave of mental health treatment. President John F. Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Act in 1963, aiming to switch national policy away from institutionalization and toward community care. Under the act, states would receive federal funding to build centers to provide treatment and diagnosis services for the mentally ill in their own communities.

People were released from state psychiatric hospitals in droves.

But the community centers were never adequately funded. And in 1981, President Ronald Reagan’s Omnibus Budget and Reconciliation Act created block grants for community mental health centers as federal mental health spending decreases.

Funding for community services shrunk, forcing more Texans to turn to state hospitals for help.

The beds continued to disappear. In 2003, the system suffered a devastating, $100 million budget cut to community mental health services. At the same time, lawmakers narrowed the scope of who can receive care from local mental health authorities and passed a bill streamlining the process of finding people incompetent in criminal cases.

The impacts were immediate. The number of mental health diagnoses in the ERs and health clinics at 20 Central Texas hospitals jumped 79 percent between 2003 and 2004, according to a 2011 report conducted by Health Management Associates.

And a Texas Association of Counties survey showed that jail health care expenditures also started to increase in counties with 1 million or more people.

By 2005, state hospital capacity had reached “crisis levels,” according to a December 2006 joint Senate committee report.

Some of the state hospitals were over capacity. The waitlist had reached 200, the report stated.

Gov. Rick Perry then approved a request from the Department of State Health Services for an additional $13.4 million for DSHS to fund 240 more beds. Those beds filled up quickly.

As people struggling with mental illness languished in jail for months, advocates sued the state for due process violations. The legal actions have dragged on for more than a decade and now include a class-action lawsuit involving more than 600 plaintiffs.

In 2008, lawmakers pumped $3.5 million into pilot programs that allowed competency restoration outside of an inpatient psychiatric hospital setting.

But the patients kept coming.

Eventually, one of them was Don.

***

Don Wallace and his wife, Ann — known by friends and family as “Doodie” — kept a close watch on their son as he struggled with his illness. They rented apartments in his name and made sure he was committed to a private psychiatric facility if there was ever any trouble. But sometimes there was a waitlist for a bed when it was time for Don to get inpatient treatment. It made the situation that much harder.

Don was never violent, but he wouldn’t always take his medication. He was prone to fits of paranoia, anxiety and delusions.

He plastered the windows of his apartment with newspapers so the government couldn’t spy on him and once drove all the way to Las Vegas, on a mission from God to stop something bad from happening.

With each breakdown, Don grew more fearful of police. When he would spiral out of control, his family would have to call for help to get him taken away for treatment.

Don knew what that meant. He was terrified of being trapped at a hospital with strangers.

So, he ran. He fought back. One time, the officers chased him around the dining room table until he tried to jump over it to escape out the door.

He screamed and cried and begged his parents not to send him back to a psychiatric hospital. He insisted he was fine. But they knew he wasn’t, even though it broke their hearts.

Meanwhile, the waitlist continued to grow. In 2011, the state established a program where Local Mental Health Authorities purchased inpatient beds at private psychiatric hospitals using state funds. At the end of 2012, there were 123 people on the waitlist.

During the 2013 session, lawmakers pumped an additional $300 million into mental health services, targeting almost $50 million to eliminate the waitlist for community mental health services, which had burgeoned to 5,200 adults and 190 children.

They also established a program that aimed to help people regain competency while still in jail. By the end of 2013, there were still about 100 people on the waitlist.

***

Don’s parents stood in the middle of a Harris County courtroom in August 2014, trying to contain their shock and frustration.

Judge Jay Burnett had just ordered Don, 55, be sent to a state psychiatric hospital for 120 days to restore his competency. He’d thrown a rock through a liquor store window after the owners denied him a job and had taken a swing at the police officer who responded to the call.

Don’s parents had offered to pay for the window. They tried to explain to the court that Don was off his medication and scared of police. They tried to show that he’d never been violent.

Don had already been hospitalized 13 times. He would never regain competency to stand trial: It had been 20 years.

The judge disagreed.

Don’s father was worried. He’d occasionally visited the state-run mental hospitals when his patients were sent there. He never wanted his son there.

Don was transferred to Rusk, three hours from home.

Frantic, Don’s mother, Ann, penned a letter to the court in September 2014, begging for her son to be released to her and her husband.

They hoped to have Don transferred to a private facility closer to their Houston home. They were willing to pay, she wrote.

No one responded to her letter, the family said.

Judge Burnett could not be reached for comment.

***

On Jan. 12, 2015, just days before Don was scheduled to be released from Rusk, he paced back and forth in the cafeteria. It was a coping mechanism he’d developed to deal with the seemingly endless days of confinement.

Police, state and court records reflect this scene: It was around 6 p.m. Patients filtered in and out of the room. Sitting at a nearby table was Jimmy Dale Mathis, 51, who previously was found incompetent to stand trial in 2013, after punching a woman who worked at a residential treatment center and halfway house in Austin in the face the year prior. He was again found incompetent in 2014 on a felony charge after striking a female detention officer on the chin when she tried to deliver his mail at the Harris County Jail. This was his second stint in a Texas mental hospital for assault after being found incompetent to stand trial.

Initial reports to Rusk police allege that Don aggressively charged Mathis and bumped into him, which prompted Mathis to push him away in a defensive manner. But a description of the video recording of the incident paints a different picture.

In that recording, Don had largely avoided the other patients as he paced back and forth.

He interacted with Mathis at least once before bumping into him, documents allege, and they exchanged words.

Mathis jumped out of his seat and punched Don in the head, records allege.

Don crumpled instantly. Unconscious, he was rushed to the emergency room.

Police weren’t called until the next day.

When police asked a hospital employee about the delay, he “was unable to provide an answer as to why law enforcement was not contacted directly after the incident had taken place,” the police report said.

Rusk State Hospital was one of five state-run mental health facilities deemed in such bad shape in a 2015 report that repair wasn't a realistic option. (Staff file photo)

***

Don was unconscious and unresponsive when his family arrived at the hospital.

The staff warned them not to expect him to regain much function.

Still, his ex-wife, Kathy, stood at his bedside, begging him to respond.

“Don?” she said through tears. “Can you hear me?”

Even though the couple had divorced in the early 1990s, she had stayed close to his family. Don saw his daughter every year. They swam in his parents’ pool. They played board games. It was like two kids having the time of their lives, his father said.

To Kathy’s shock, Don opened his eyes.

His eyes followed her when she moved. He responded to her commands. He tried to talk, but the ventilator made it impossible.

Doctors told the family Don’s brain injury was significant. While in the hospital, his fever had spiked to 103 and he developed pneumonia.

But he was awake.

His family explained where he was; that he had gotten hurt at the hospital; that doctors were doing everything they could.

His parents made plans to transfer him closer to home.

His father fired off a letter to Brenda Slaton, superintendent of Rusk State Hospital.

He wanted answers: Who was investigating? Would charges be filed? How could he see the video footage of the assault?

Then, days after he first opened his eyes, Don’s organs started to fail. Doctors induced a coma.

He died on Jan. 28, 2015, with Kathy and his daughter at his bedside.

***

Days turned into weeks. Weeks into months. And still, the state had not reached out to the Wallaces about Don’s death.

“We’ve received no answers,” his sister said.

Months later, in May 2015, Don’s family received a response.

The state wanted to keep some of the information confidential and had sought an opinion from the Attorney General’s Office.

The attorney general largely agreed.

Following Don’s assault, the state had formed a “Rusk State Hospital Root Cause Analysis Peer Review for Sentinel Events Oversight Group” to analyze the cause of the incident as required by accreditation standards of The Joint Commission, a nonprofit that accredits more than 20,000 health care organizations nationwide.

According to the attorney general, that oversight group was considered a “medical committee,” and any records from it were confidential and not subject to a subpoena.

“The family isn’t privy to the findings — it’s all confidential,” said Beth Mitchell, senior attorney for Disability Rights Texas. “It really sucks for the family.”

Mitchell said she believes the confidentiality centers around the state not wanting to be sued. But transparency is needed, she added.

“Ultimately there has to be some transparency in terms of knowing when that does happen, are they really fixing the issue?” she said.

The Chronicle also requested these documents but was denied.

Whitmire wasn’t surprised that the Wallaces didn’t receive answers, he told the Chronicle: It’s difficult if not impossible to find out what goes on in state hospitals.

But he said there should be better mechanisms in place to find out what happens to your loved one in the hospital.

It’s unclear if the state ever sent the group’s findings to the Joint Commission. The commission “encourages” hospitals to self-report incidents concerning patient safety, said Maureen Lyons, spokeswoman for the organization, but it is not required.

If the incident is not reported directly to the commission, she added, it still can review and evaluate it based on information from federal and state agencies or “media coverage or reporter inquiries,” she said.

Lyons could not tell the Chronicle if Don’s death was reported to the commission because those records are not retained or available after three years.

***

Mathis wasn’t arrested in Wallace’s death until about a year and a half later. He was charged with murder.

By that time, he had been released from Rusk.

The Cherokee County district attorney at the time, Rachel Patton, now works in the Texas Attorney General’s Office and could not be reached for comment. Her successor, Elmer Beckworth, said he was unsure what caused the delay.

Mathis soon was deemed incompetent to stand trial. A judge ordered him committed to a state psychiatric hospital for competency restoration.

But the waitlist for a maximum security bed was pushing 300.

While in jail, Mathis told psychiatric evaluators that Saddam Hussein was his brother. He was hearing voices, he said, and had visions of dead people attacking him at night.

“Patient has a long history of mental illness and has not shown clinical improvement,” one evaluator wrote in March 2017.

Nine months later, in December 2017, he was finally transferred to North Texas State Hospital, one of the state’s two maximum security psychiatric facilities.

More than a year later, Mathis was still at North Texas and exhibiting some of the same psychiatric problems he faced prior to admittance. He told psychiatrists in March 2019 that he heard voices all the time and that he didn’t want to take his medication. He saw dead people trying to cut people’s throats. He claimed that he was God and that he heard Satanic voices.

“His speech is rambling and illogical. Most answers to questions are non sequitur or nonsensical,” one examiner wrote. “He has no insight and his judgement is impaired by his psychosis.”

He also was still exhibiting aggressive tendencies. That month, he had grabbed a female staff member’s rear and then hit her in the face. He had to be restrained.

Both psychiatrists recommended that Mathis remain in maximum security.

But in November 2019, his case was reviewed by a secretive panel, known as the Dangerousness Review Board, that determines the correct security setting for mentally ill individuals committed to maximum security.

That panel determines if someone is or is not manifestly dangerous — and if they are not, they must be transferred to a less-secure state facility.

HHSC does not track how many people who are transferred from maximum security to a less-restrictive setting are later accused of injuring other patients or staff, officials said. There is a process, however, that allows hospitals to send patients back to maximum security if they are causing problems. Between 2014 and 2019, that happened fewer than 30 times.

The panel decided that Mathis was not manifestly dangerous — citing adherence to his psychiatric medication regimen, lack of physical aggression or restraints and controlled psychiatric symptoms — and was therefore ready for a less-secure environment. It’s not clear how such a drastic change occurred.

Mathis was sent back to Rusk.

***

In June, Mathis struggled to answer basic questions during a hearing with Cherokee County Judge R. Chris Day.

“I need you to listen carefully,” Day said to Mathis.

After five years in and out of the state’s mental health system following the assault that led to Don’s death, Mathis had finally been found competent to stand trial.

And he wanted one.

“I want a trial,” he repeated over and over.

“You want a trial?” Day asked. “You want me to consider you not guilty?”

This was clearly not what Mathis’ attorney, Jeff Wood, had told the judge to expect.

Looking frazzled, Wood asked to speak privately with his client.

They returned about 30 minutes later. Mathis entered a plea of “not guilty by reason of insanity.”

Wood did not respond to repeated requests for comment. The Chronicle attempted several times to speak to Mathis when he was in jail, but he would not come to the phone.

Mathis was sent to a state hospital in September 2020, but the Cherokee County Jail did not know to which hospital he was admitted.

***

Desperate, the Wallaces took steps to sue the state. Several attorneys said there was nothing they could do.

Mitchell told the Chronicle that the only way a family could sue the state is if it failed to uphold constitutional standards, such as due process rights — that means someone can’t simply sue the state for neglect.

“You’d have to show that they were deliberately indifferent, and that’s a really high standard,” she said.

When Don died so young, his parents couldn’t bear burying him in the family plot. So, they had him cremated instead and put his ashes in a stately black clock. It sits on his father’s desk, ticking off the moments until they will be together again.

A patient makes her bed at Rusk State Hospital in 1967. Nearly 50 years after this photo was taken, Don Wallace was assaulted in this same hospital by Jimmy Dale Mathis. He later died from his injuries and Mathis was charged with murder. He pleaded Not Guilty By Reason of Insanity in June. (Richard Pipes, Staff file photo | Houston Chronicle)

Support our journalism

Help our journalists uncover the big stories. Subscribe today.

Alex Stuckey is an investigative reporter for the Houston Chronicle and joined the paper in 2017. That same year, she won a Pulitzer Prize after unearthing the rampant mishandling of sexual assault cases at Utah colleges and universities while working at the Salt Lake Tribune. She is an Investigative Reporters and Editors award winner and a Livingston Award finalist. You can reach her at alex.stuckey@chron.com and follow her on Twitter @alexdstuckey.

Mark Mulligan is a staff photographer for the Houston Chronicle, where he takes pictures and flies the Chronicle’s drone. A native Houstonian, he previously worked at newspapers in Virginia and Washington State before moving home to Texas with his family. Follow him on Twitter @mrkmully and Instagram, or reach him by email at mark.mulligan@chron.com.

Design and photo editing by Jasmine Goldband.

***

"how" - Google News

February 25, 2021 at 11:00AM

https://ift.tt/3dL22lh

How Texas fails the mentally ill - Houston Chronicle

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How Texas fails the mentally ill - Houston Chronicle"

Post a Comment