Transitioning from being a postdoctoral researcher to a laboratory leader comes with a suite of challenges. Not only do new principal investigators often have to relocate to a new city or country, but they also have to acquire funding, recruit lab members, teach, launch research programmes, develop outreach initiatives and complete administrative duties. These pressures have been amplified by the pandemic. Five new principal investigators share their experiences and advice for other rookie lab leaders.

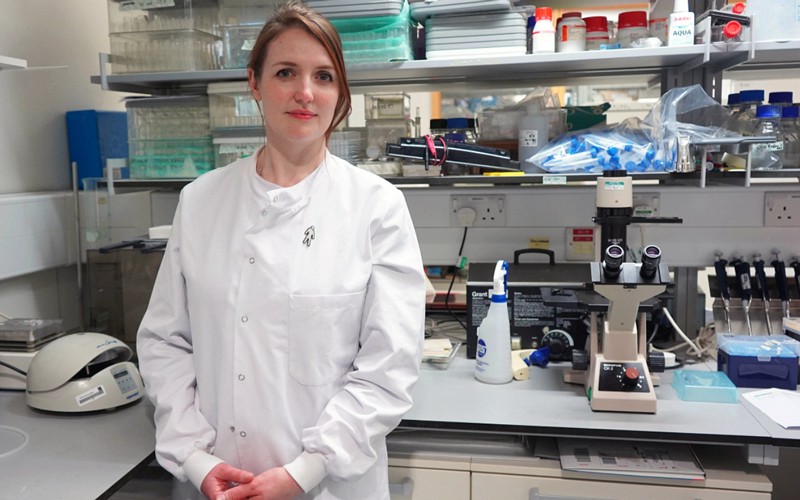

EILEEN PARKES: Share your experiences

Immunologist and junior group leader at the University of Oxford, UK.

I’m a first-generation university student, so the idea of uprooting and moving for a particular role, which is so normal in academia, isn’t something my parents or others in my family could really understand. Uprooting isn’t easy on anyone, but it’s even harder with children and a partner. Organizing childcare, schools and a new home while everything in the world was working differently because of the pandemic added an extra layer of complexity. My husband moved his job so we could stay together — no small achievement. Establishing yourself and building a new lab is challenging for early-career researchers, it is extra challenging when your family is also getting established.

I started my lab in September 2019 and the first person I hired joined the following month. We had hit our stride in February 2020. We went from empty benches to having all the reagents we needed, and we re-optimized all our assays for our new equipment — a typical job in a new lab. It felt like I fell off a cliff edge when labs closed in late March 2020. I had a real sense of being adrift and not knowing what was going to happen.

The first lockdown in the United Kingdom started in late March and lasted, in some form, for several months. I wasn’t prepared for how quickly the shutdown happened and for how long it would last. As a medical oncologist, I continued running early-phase trials to test new anticancer drugs, but our lab work on tumour immunology stopped when staff were furloughed, or put on temporary leave by the university.

As part of the UK government’s deal with employers to cover a percentage of wages during the furlough period, we were not allowed to check e-mails or contact colleagues professionally. By that time, I had recruited two postdocs, two PhD students and a technician. It was especially challenging for them because there was so much uncertainty about their research and future careers, but I couldn’t do anything about it. I was quite open with funders about the challenges and made sure that lab members felt supported and reassured. The UK furlough scheme was great because it could be used to support staff. Because it was my first time managing a team of people, I had to learn how to tell my staff they were valued, but that they couldn’t work for a few months because of the furlough scheme. I just keep saying, “You started a PhD in a pandemic, this can only get better.”

As a new principal investigator during the pandemic, I knew it was going to take a few years to build momentum, but I still had this feeling that I was standing still while everyone else was racing ahead. I kept reading about principal investigators who were writing papers and doing massive amounts of data analysis, but I had just opened my lab — I didn’t have loads of data to analyse.

What really helped was talking to other people who were at a similar stage. I love meeting people and discussing ideas, so I have a lot of friends in science who I can reach out to. I also have a network of mentors, some of whom are my peers and others who are more senior. Running a lab can be lonely. Thankfully, I have excellent colleagues around the world who I can talk to and share my experiences with.

ALYCIA LACKEY: Let go of guilt

Evolutionary biologist and assistant professor at the University of Louisville in Kentucky.

I started my lab in August 2020 and I am still working on making the lab space feel more like mine. Right now, it’s just one undergraduate student who started in January, and me. She’s doing research for course credit and spends about six hours a week in the lab. She’s currently helping me to set up the lab and to build research equipment that we’ll need in the summer. My lab studies how animal populations respond to rapid environmental change, including climate change. I typically do fieldwork in the midwestern United States during the summer, but I’m trying to be flexible about travel plans this year because of the pandemic.

When I started my lab, I asked a lot of people for advice so I could work out how to prioritize tasks. Although the advice was great, I burnt out trying to follow everyone’s recommendations. It took me a couple of months to realize that as a principal investigator, I get to define what’s important to me within the bigger context of producing research and teaching. I had to let go of feeling guilty that I couldn’t do it all. Being a new lab leader is an intense job, but I also had to deal with the pandemic and the social unrest in the United States, including the racial injustice that hit a peak in public awareness last summer. It was a lot to process.

I started structuring my calendar by assigning blocks of time to tasks I identified as priorities. In the beginning that mostly involved meetings and teaching. It takes me a long time to put together materials for undergraduate classes that I’ve never taught before, so I needed to block out time for that. Meetings with collaborators, students and administrators fill up my schedule too. I realized I needed to carve out time for writing and research planning. Every week, I make a list of goals and then map them onto the calendar. For instance, I try to spend four or five days a week writing papers and grant proposals.

Developing a reward system also really helped me. When I complete a task, I get a little sticker on my calendar, which seems silly but it’s really fun to see a calendar covered in little alligators at the end of the month. At home, I have a wall covered in papers that celebrate my big and small accomplishments, such as grading an exam or sending a manuscript to a collaborator. In those moments when I think I didn’t get anything done during the week, I look at the wall and see that I have made progress.

RACHEL LIPPERT: Find new ways to connect

Neuroscientist and junior research group leader at the German Institute for Human Nutrition, Nuthetal.

I sprinted out of my postdoc into a group leader position in February 2020. It was a chaotic start, partly because my only housing option was a 10-square-metre room in the attic of a local house share, which I found through a German website for finding room-mates. I didn’t bother unpacking because I thought I’d find an apartment to rent quickly. Then Germany went into lockdown from March until early June.

Lab work slowed down during the pandemic. My research focuses on the effects of maternal obesity and overnutrition on offspring brain development using mouse models. The university didn’t want us to start new experiments and the mouse facilities were split over two locations to reduce interactions between caretakers. Germany went into a second lockdown in November and many measures are still in place now. The mouse facilities are still not fully functional.

There are currently three postdocs, two PhD students and a technician in my lab. Because it’s a new lab, there’s only so much work people can do from home when we haven’t collected much data yet. We’ve been able to collect some imaging data, but it’s limited compared with the scope of our research before the pandemic.

One of the most difficult aspects of the pandemic is that we have very few interactions with other research groups. I was eager to find ways to keep my lab members connected to other scientists, so I organized a digital journal club with some of my former colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research. It’s been great for my lab group to not only discuss neuroscience and receive feedback on their ideas, but also have an opportunity to connect with other researchers on a personal level.

It’s also been really important for me to lean on my support networks to navigate this experience. Because everybody is having a hard time right now, I try to be open so people can vent to me when things don’t work out and I’m grateful that I can vent to them, too.

My advice for new lab leaders is to keep in mind that there are positive things that come from going through difficult experiences. For me, it was starting a small network of new principal investigators in Germany and building relationships with other colleagues. Don’t be afraid to reach out to someone to say, “I think we have something in common, can we chat for ten minutes?” Right now, more than ever, people are looking for ways to connect.

MARTIN STEINEGGER: Start a joint lab meeting

Martin Steinegger is a computational biologist and assistant professor at Seoul National University.

I moved to Seoul in February 2020 from Baltimore, Maryland, where I was doing a postdoc at Johns Hopkins University, and started my lab a month later. I hadn’t heard of any reported COVID-19 cases when I left the United States, but cases in South Korea were spiking. Thankfully, South Korea handled the situation very well. For most of the pandemic, it was possible to be in the lab with my students.

Before I moved to Seoul, I posted on Twitter that I was looking for postdocs and PhD students to join my lab and had applicants by the time I arrived. Currently, there are seven people in my lab: one postdoc, two graduate students, three interns, and me. My lab focuses on developing software to analyse biological data, particularly genomics data collected from the environment, such as soil or ocean samples. There is so much species diversity in these samples that current software programs can typically only assemble 20–30% of the DNA data collected, meaning the majority of information isn’t being used. Because my lab mainly does computational work, members can work from home and choose their schedules.

The pandemic has made it challenging to integrate into the new department. I don’t have a big network in South Korea and I don’t speak the language fluently, which was already a barrier to meeting people. Since moving here, I try to spend four to five hours each week learning Korean. I took a Korean class offered by the university and hired a private tutor — I pay for both. Korean is a very difficult language, and most documents, e-mails, grant applications and websites are in Korean. Now that faculty meetings and seminars are online, it’s even harder to strike up a conversation or arrange to go out for a meal.

My advice to new lab leaders is to establish joint group meetings with other peers as early as possible. In my case, I joined a workspace for my field on the communication channel Slack, and the new principal investigator Slack channel, where you can discuss the day-to-day challenges of being a lab leader. It’s crucial to ask for help if you’re struggling. Before the pandemic, I could just ask someone to join me for a coffee, but now I don’t have the luxury of bumping into somebody that might solve my problems. I realized I had to be more active about reaching out to other researchers. I’m still in touch with my previous supervisors. After nearly a year, I still only understand basic things in Korean, but my department helped me by hiring an administrator to support me.

AIKO SADA: Be patient

Cell biologist and associate professor at Kumamoto University in Japan.

When I started my lab in October 2019, it was just me and an empty lab space. I didn’t even have benches until the following March. The department has open laboratories that are shared between a few faculty members, so although my portion of the lab was empty, I could set up a small table in a shared space to work. My research focuses on how different populations of stem cells affect skin regeneration and ageing. A professor I knew from my former position at the University of Tsukuba, Japan, kindly kept my mice there, which allowed me to continue my experiments while I was setting up my new lab.

It took me about six months to order new research supplies and unpack everything. The pandemic added an extra challenge because I couldn’t order or import some materials I needed, such as culture media and antibodies. In the beginning, gloves and masks weren’t available, and even now, they’re nearly twice as expensive as they were before the pandemic. I was able to order general biomedical materials, such as enzymes, from domestic companies.

Now, my lab has two postdoctoral researchers, two PhD students and a technician. In May 2020, Japan implemented a two-week lockdown. My lab is in Kumamoto, which is in the countryside, so it was relatively less affected by COVID-19 than universities in the cities. We worked from home and took turns coming into the lab, which made it difficult to talk about ongoing experiments. When the lockdown ended, everyone came back into the lab again.

Even though we can all be together now, I feel sorry that the new lab members haven’t had a chance to interact the way we could before the pandemic. We can’t have lab parties and it’s been harder to communicate with people in other research groups.

The pandemic has also made it challenging to recruit people to join my lab. New principal investigators often have fewer applicants for open positions compared with more established researchers because they have to set up everything from scratch. On top of that, Japan stopped issuing visas in April 2020 owing to the pandemic. It started issuing them again last October, but the process is very slow for postdoctoral researchers and PhD students. There were a few short-term postdocs from China that were supposed to come work with me in Japan, but they couldn’t get visas even though they secured funding to cover their expenses. I have another PhD student from China who was supposed to start in April 2021, but because of the pandemic her parents didn’t want her studying abroad.

Although it’s been a difficult time to start a lab, it’s been helpful to talk to other new principal investigators about their experiences. There’s a group for young principal investigators at my university, at which we talk about our research programmes, share materials and ask each other questions. We can go out for lunch in small groups, but we don’t go out for drinks like we did before the pandemic.

It’s been tough having fewer people and fewer materials as a new lab leader but setting up a new lab takes time. At first, I felt a lot of pressure to produce data and write papers and grants on top of doing required paperwork, recruiting people and purchasing laboratory equipment. Now I understand that it will be a little while before I publish my first paper from my own laboratory. My advice is to be patient. The pandemic has been tough as a new lab leader, but it also gave me time to think about my research. By giving talks, attending seminars and meeting new people online, I broadened my ideas and developed new projects and collaborations.

"how" - Google News

May 17, 2021 at 07:39PM

https://ift.tt/3w94t6Y

How new principal investigators tackled a tumultuous year - Nature.com

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How new principal investigators tackled a tumultuous year - Nature.com"

Post a Comment