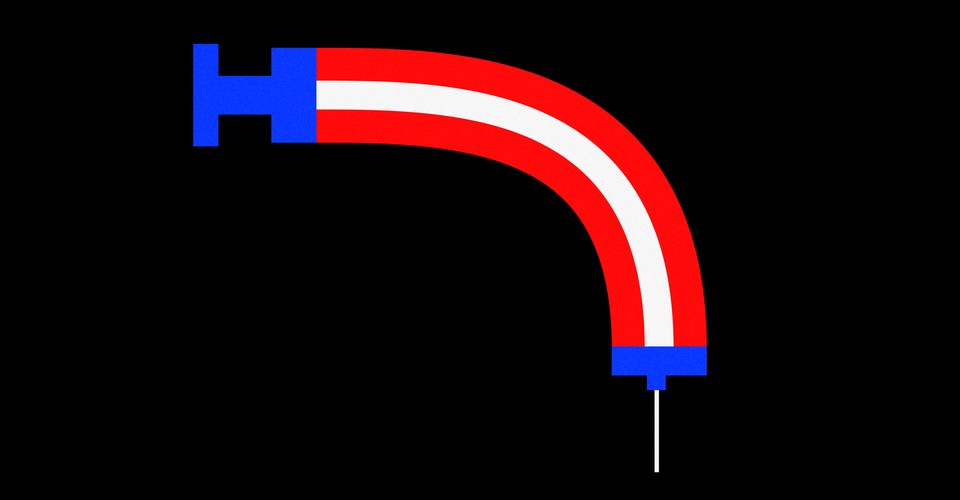

In April, when I received my second Moderna shot, America was on a roll. Adjusted for population, the United States had distributed more COVID-19 vaccines per capita than any country but Israel, Chile, the United Kingdom, and a smattering of small nations and islands. With a surge of doses, we could have been No. 1 in the world.

Five months later, the U.S. is no longer in the top five in national vaccine rates. We’re not in the top 10, or the top 20, or top 30. By one count, we’re 36th—countries as varied as Malta, Canada, Mongolia, and Ecuador have all surpassed us. If the European Union or the G7 were countries, they would be ahead of us too. With about 66 percent of Americans over 18 fully vaccinated, some might be impressed that it's possible to get two-thirds of the country to agree on anything. But America still seems to suffer from an internationally unique reluctance.

How did this happen? The U.S. was arguably more responsible than any other country for the invention, manufacturing, and distribution of the mRNA vaccines. How did the pace-setting effort to vaccinate Americans peter out and leave us behind most of the developed world?

I’ve tried to solve the mystery of the vaccine slowdown before, but I don’t think many of the old popular explanations hold up. This spring, it was briefly fashionable to blame the FDA’s mixed messaging around the side effects of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. But European countries, including the U.K., dealt with similar vaccine pauses with AstraZeneca, and they’re now miles ahead of us in vaccination rates. So that can’t explain everything.

Some have argued that U.S. public-health officials downplayed the effectiveness of the vaccines, which hurt vaccine uptake. I agree that messaging from the CDC and other institutions has been overly neurotic and often confusing. But many leaders throughout Europe emphasized the vaccines’ side effects on their way to achieving higher total vaccination numbers. So trepidatious sci-comms might not be a major factor either.

Instead, the data point to three key reasons the United States is 36th and falling: It is unusually uninsured, unusually contrarian, and unusually polarized. These are three familiar—even defining—attributes of American life.

A sizable proportion of unvaccinated Americans aren’t unpersuaded and skeptical but rather uninsured and scared. Polling from the Kaiser Family Foundation indicates that no group is more likely to reject the vaccines than young Americans without insurance. Members of this group are disproportionately young and low-income and lack easy access to a doctor if something goes wrong. Many of them don’t know that the vaccine is free. Meanwhile, the fear of side effects is one of the most common reasons people give for avoiding the vaccines. This fear, compounded by a feeling of estrangement from the health system, is clearly keeping many Americans from getting vaccinated

But something else is going on, according to Michael Bang Petersen, a Danish researcher who led the Hope Project, a large international survey of global attitudes about COVID-19. He told me that Americans aren’t radically different from Europeans on how much we trust public authorities or how readily we accept public-health restrictions to fight the pandemic.

What makes the U.S. exceptional, he said, is our unusually low support for vaccines in general. The U.S. had significant levels of vaccine hesitancy before the pandemic, and Petersen’s research found low acceptance of the vaccines in 2020, before their authorization. While support for the vaccines exceeded 70 percent in countries like Denmark and the U.K. last year, only about half of Americans consistently expressed interest in being inoculated.

America’s historical contrarianism about vaccines has many potential sources. Uninsured people who can’t afford to see doctors may be conditioned to trust in their body and hope for the best. A history of medical racism has coincided with lower trust for novel treatments among Black Americans. But not all American vaccine skeptics suffer from discrimination or a lack of resources. Perhaps a country whose laws and culture celebrate independence of thought might naturally yield a bimodal distribution of contrarians: lots of paradigm-breaking entrepreneurs and scientists on one side, and lots of conspiratorial cranks on the other.

That leads to the second part of Petersen’s explanation: America’s vaccine attitudes are unusually politicized. “The level of polarization between Democratic and Republican elites seems unique to me,” Petersen said, “and it’s a leading factor in why American vaccination rates are relatively low.”

The U.S. is distinctly unlucky in having a polarized two-party system, in which one party’s elites take up vaccine resistance as a prominent cause. While GOP governors and even former President Donald Trump have admitted to being vaccinated and occasionally recommended the shots, the party’s most significant media organs, including Fox News, have consistently questioned the benefits of the vaccines, amplified the side effects, celebrated evidence-free skepticism, and blasted attempts to promote vaccinations. Today, Florida Republicans aren’t just claiming that the vaccines are faulty. They’re reportedly looking to rescind measles- and mumps-vaccine requirements. Negative polarization has fully overtaken the right wing of the Republican Party, whose ethos is now something like “Whatever liberals say, I’m against” and whose members stand ready to embrace the most absurd conclusions of that logic.

I asked Petersen how Democratic leaders such as President Joe Biden or public-health officials such as Anthony Fauci could help solve this problem. His answer was not comforting. “Many conservative Americans have simply lost trust in and tuned out public-health communicators, and that’s very hard to solve, because when a population loses trust in the messengers, the content of the message doesn’t matter,” he said.

Petersen’s interpretation has subtle, and potentially depressing, lessons for liberal pandemic commentators, including me. I would love to think that my analysis of the pandemic can convert the unvaccinated, just as many journalists imagine themselves to be frontline soldiers in an information war. For months, journalists and the epidemiologists they follow on Twitter have been energetically discussing the best way to represent the benefits and risks of vaccines. But these debates were held among people who were almost entirely vaccinated and whose friends and families were almost entirely vaccinated. Meanwhile, the truly hesitant were elsewhere—watching Fox News, exchanging side-effect rumors on Facebook, or marinating in conspiracy theories in other pockets of the internet. Mainstream outlets can always improve their coverage, but they cannot change the mind of people who ignore them. If traditional media criticizing public-health messages in other traditional media isn’t quite preaching to the choir, it’s at least screeching among the choir.

“Trust is a resource that you draw upon in a crisis,” Petersen told me. “It’s much harder to build trust as the crisis is ongoing.” The same could be said for institutions, policy, and culture. In a pandemic, you go to war with the country you’ve got, and you learn what kind of country you’ve got only after you go to war. Underinsured, paranoid, and polarized, the U.S. rolled into 2021 with a uniquely impenetrable bedrock of vaccine skepticism.

Americans didn’t fall behind the developed world in vaccines so much as we started with major disadvantages that became more and more apparent as time passed. Today’s vaccination numbers are a lagging indicator of America’s many preexisting conditions.

"how" - Google News

September 26, 2021 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/3zGCblF

How America Lost Its Lead on Vaccination - The Atlantic

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How America Lost Its Lead on Vaccination - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment