Thirty years after its release, Seattle rock trio Nirvana's breakthrough album Nevermind retains an evocative power. When I hear its opening notes, I'm rocketed back to a teenage house party in suburban London; in that darkened parlour, I could feel guitars and machines fighting for my soul.

I was thrilled by Nevermind's sounds, but as a young music obsessive (who also happened to be a Muslim female Iraqi Brit), I felt sidelined by the press coverage around the record, and Seattle's burgeoning "grunge" scene; mainstream perspectives seemed overwhelmingly blokey, homogenously white and insular – at odds with Nirvana themselves, particularly their culturally inquisitive, masculine/feminine frontman Kurt Cobain. As Nevermind hits its 30th anniversary, I was curious to discover how the album personally affected fans and musicians around the world. These varied global exchanges (much aided by modern tech) reinforced Nevermind's classic album status; like all great pop culture, it fires shots across distance and time.

More like this:

- An anthem that stuns each new generation

- Our most misunderstood love song?

- The music that won't be silenced

While I discovered Nevermind in early-'90s London, Mahdis Keshavarz was a 15-year-old Iranian-American riot grrrl living in Seattle. Keshavarz is now a NYC-based media strategist, human rights activist and founder of media firm The Make Agency, but back then, she was booking indie gigs at the Old Fire House Teen Centre in Redmond, near Seattle: a pioneering city initiative where youth were enabled to reclaim and run community space. She was already familiar with Nirvana; some time before, a schoolfriend had handed her a tape by his cousin Kurt, who'd been crashing in his basement ("It was a black cassette tape with the title 'Bleach' [Nirvana's first album] in white-out [pen]. I listened, and it was just bonkers and really cool," she smiles).

Keshavarz describes the transformative atmosphere of the Old Fire House ("We got to use that space as young people wanted, so invariably it became a political space, a music space, a gathering space"); it was also frequented by varied musicians, including members of Dinosaur Jr, riot grrrl pioneers Bikini Kill, Kris Cornell, and Cobain. "We were so righteous in our punk rock-ness; the music was special, but it was also a philosophy: wanting to be radical feminists, carving out a space for ourselves in a time that was so predominantly male, also teaching men how to be feminists and allies. Kurt was one of them," says Keshavarz. "For me, being a woman of colour and a Muslim woman was both profoundly alienating and also a path to finding a space. At high school, there was no space to be subversive. Punk rock was where I felt most at home."

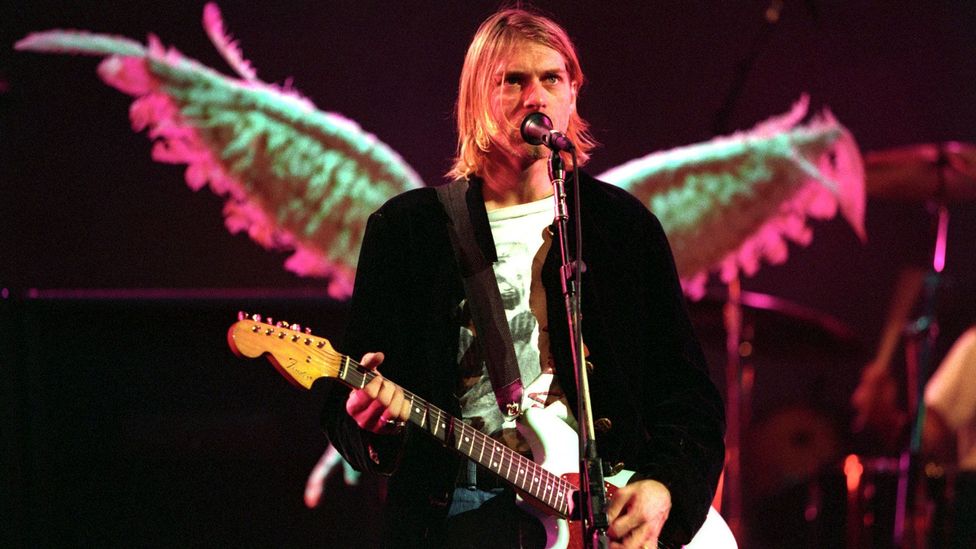

Keshavarz met Cobain in Seattle, and found him a 'gentle soul' (Credit: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic)

When Nirvana released Nevermind in September 1991 (on major label Geffen, following the band's emergence on Seattle indie SubPop), the album's explosive success followed a European tour and proved a shock to the mainstream system (Geffen president Ed Rosenblatt described it as "one of those 'get out of the way and duck' records"). Back on the Seattle DIY scene, the mood was less celebratory: "My memory of Nevermind is that it felt like a betrayal," says Keshavarz. "People were protective because Nirvana were representative of a community and so many ideas. In retrospect, I have great sympathy for the band, because I think they legitimately made beautiful music that touched people's hearts. In fact, I remember visiting Iran soon after Nevermind came out, and smuggling in tapes to play to friends and relatives; you'd see their faces, like: 'What is this? It's kinda cool… can I get a copy?'

"But within Seattle at the time, people were super-upset; it was that DIY ethic that believed you couldn't achieve liberation through a major label. We knew rents and ticket prices would go up, and we were really protective of our spaces. Kurt would often turn up at the Old Fire House and just be quiet in a corner; he was a gentle soul, and everybody loved him – yet sometimes, he wouldn't be welcome, depending on who was playing, because the anger levels were high. That must have been hurtful."

Global reverberations

Nevermind has reportedly sold over 30 million copies worldwide, making it one of the biggest albums in music history. It also arguably forged a kind of globalised youth culture, fuelled by the increasing reach of MTV (which had its videos, including Smells Like Teen Spirit, on heavy rotation). Brazilian cultural studies academic Moyses Pinto, now a professor at Lutheran University in Porto Alegre, was struck by Nevermind's initial release when he was 11. "I thought: 'this is perfect'; it sounded like a bright synthesis of noise and pop music," he says.

Neto points out that Brazil's military dictatorship (1964-1985) inspired many rebellious musicians, including pysch-rockers Os Mutantes (one of Cobain's favourite bands). The end of the dictatorship extended the range of rock, punk and post-punk sounds in Brazil, though Neto describes a "time lag" between international influences, before the age of Nevermind: "We had punks in Brazil, but almost a decade after their peak in the UK and US – and there was '80s pop culture and mainstream arena bands," says Neto. "But the impact of Nirvana and MTV made it synchronised; a new youth – including me – began to hear the same music, and wear the same styles; there was a cultural homogeneity probably never experienced before. Grunge culture became dominant very quickly; all that had been 'cool' suddenly became ugly and exaggerated, and Kurt was the symbol of transgression."

Another Porto Alegre kid in '91, Rogerio Maia Garcia, was intrigued by Nevermind's "swimming baby" vinyl artwork (the album arguably heralded an era of visual iconography, as well as musical influence), right before the music captivated him: "We were all listening to rock and metal, but Nevermind sounded totally different – like 'normal kids' playing at home: raw, and really loud," says Garcia. "It certainly opened our ears to the grunge scene; after Nevermind, bands like Soundgarden, Alice in Chains and Pearl Jam became well known in Brazil, and many kids started learning to play; in early '90s Porto Alegre, live music had been losing out to dance music, but suddenly there were local band gigs every night." He adds that established Brazilian bands such as Titas also incorporated the influence, working with Seattle producer Jack Endino for their own album Titanomaquia (1993).

Garcia grew up to be a criminal lawyer rather than a full-time musician, but he remains an ardent Nirvana fan: "In my mind, Nevermind's legacy can't be separated from Kurt Cobain's last years of life [Cobain was just 27 when he took his own life in 1994]," says Garcia. "I later realised that his voice expressed a sad violence and emptiness over life experiences; songs like Lithium took a new perspective. I think Nevermind expressed the feelings and fears that any teen goes through, from my generation in Brazil to now."

A blend of political revolution and personal revelation also brought young music student Grzegorz Kwiatkowski (now vocalist and guitarist for acclaimed Gdansk indie rockers Trupa Trupa) to Nevermind: "We're talking about Poland in 1991, only a few moments after defeating the communist system, and the beginning of the democratic system, which brought not only cynical capitalistic stuff from the West but super high-quality stuff – like Nirvana and Nevermind," says Kwiatkowski. "For Polish teenagers, MTV was a signal that we are part of international youth."

For the Polish musician Grzegorz Kwiatkowski, Nevermind symbolised freedom after the fall of Communism in his country (Credit: Renata Dabrowska)

Kwiatkowski grew up listening to everything from Schubert to The Beatles, and saw Nevermind as a natural progression: "Very beautiful, very simple songs; the perfect combination of killer sound and great singer-songwriting". His own band would sign a worldwide deal with Seattle institution Sub Pop in 2019; Trupa Trupa continue to create original, expansive music while crediting their early inspirations. "In my opinion, Nirvana and Nevermind are still the symbols of freedom and normality," says Kwiatkoswki. "Not unreal superstardom, but something 'regular', and at the same time, great."

English remains the lingua franca of pop culture (for now), and Nevermind has inspired countless international covers. Jamaican reggae artist Little Roy released an album of reggae-fied Nirvana covers (Battle for Seattle, 2011); Brazilian tropicalia star Caetano Veloso would rework Come as You Are; Indian hard rockers Pentagram (fronted by film music composer Vishal Dadlani) would add Nirvana covers to their live sets.

Japanese music journalist Hiroko Shintani was immersed in international alt-music scenes in 1991, and already knew Nirvana's Bleach album – but couldn't initially believe Nevermind was by the same band: "My first reaction was: 'What's happened to them?!' – in a positive sense," says Shintani. "I was more shocked by the fact Nevermind went on to become such a cultural landmark, and sell that many copies. But what I admired was the innate pop sensibility that cuts through the musical style and the irony of these songs about Kurt Cobain's discomfort; his alienation from the mainstream ended up being shared by millions of people, thanks to that sensibility.

"I remember the thrill of hearing such a raw and vulnerable male voice on mainstream radio and MTV. Kurt sang: 'Never met a wise man/ If so, it's a woman' [on the album track Territorial Pissings]. That in itself was phenomenal."

Shintani notes that while Japan produced numerous home-grown rock bands in the late-'80s/early-'90s, that era's mainstream artists weren't necessarily driven by angst or social rebellion. "Remember, Japan was enjoying 'bubble economy' until the early '90s, and our 'Generation X' grew up in a relatively prosperous time," she says. "But obviously, Nevermind's legacy lived on, and I think it had much larger influence among bands that came out during 2000-2010." Indeed, 2012 saw the release of a compilation album, Nevermind Tribute, where a new generation of Japanese bands covered Nevermind's track-listing, in sequence.

Turkish musician Gaye Su Akyol discovered Nevermind when she was at primary school (Credit: Aytekin Yalçın)

Another artist who discovered Nevermind after its original release is Istanbul-based singer-songwriter and visual artist Gaye Su Akyol. She's widely praised for her fearless, politically-charged expressions (including latest album, Istikarli Hayal Hakikattir), and she cites Nevermind as a formative inspiration – it was 1995, she was at primary school, and she found her brother's cassette album in their mother's car. "I remember hearing Nevermind for the first time; it was groundbreaking!" says Akyol, adding that she badgered her brother with questions about Nirvana, learning how Kurt had died. "Probably to protect me from admiring that, my brother told me: 'He had everything: fame, money, love, but he chose to die'. I was confused and unsatisfied; I was looking at the cover art, the band's photos inside.

"I felt lucky to discover a treasure, and also remember feeling: 'this is exactly what I need!' I always had a rebellious and disobedient spirit. I was looking for a different way to express my feelings, and Nevermind caught me instantly; it opened the doors of rock'n'roll to me."

Akyol still describes Nevermind as a "homecoming" album; she has held onto the original cassette, though is now equally likely to listen to it on vinyl or digitally: "The intimate relationship I had with it is always alive, and it's a 'safe space' where I can breathe."

Nevermind made "outsider" spirit feel like a unifying experience, on a massive scale. This also struck a chord with Mpumi Mcata, co-founder of brilliantly sharp Johannesburg rockers BLK JKS; in the early '90s, Mcata had left high school to pursue his band dreams, and first heard Nevermind while working in a music shop.

"As a black boy growing up in post-apartheid South Africa, it's safe to say that what Nirvana were proposing was not what you'd expect to hear anywhere near me – but it cut through: the raw energy, the honesty," says Mcata. "Nirvana's general 'Come as You Are' ethos definitely resonated with me; it came across as simply doing what they wanted to do, or just what they could... and they still gave everyone, from limo-crashing hair metal rockers to Michael Jackson, a run for their money. This, and Kurt's politics. In my band, BLK JKS, we see more value in disrupting than in fitting in, but it's not always easy; having beacons like Nirvana is a blessing."

Mpumelelo Mcata found a kindred spirit in Nirvana (Credit: Kgomotso Neto)

In 2009, Nirvana's former drummer, Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl told Rolling Stone magazine that BLK JKS's debut album After Robots was one of his favourite records that year; in 2014, Grohl invited BLK JKS to open for Foo Fighters on their South African tour.

Mcata recalls watching Foo Fighters' sets from backstage, and feeling fired up for BLK JKS's second album (Abantu/Before Humans, released this year): "I thought about brother Dave Grohl's career after Nirvana… how incredible it was to watch them in that stadium! Then I listened back to Nevermind; it was a kick in the backside – get back in the studio, and do it for the love of music!"

Back in the US, Keshavarz (who had also helped to put on Foo Fighters' first gig in '95) now credits former Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic for helping to preserve Seattle's all-ages music scene – and she listens to Nevermind with her seven-year-old son.

"There's something about that music and moment that really speaks to the frustration and anger that you feel as young people," says Keshavarz. "I also think that now that frustration with government and 'The Man' is so much more prevalent in our lives, that the message of Nevermind is maybe stronger.

More people listen to its sentiment, and realise that Nirvana were using the music industry as a vehicle to push back."

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"how" - Google News

September 23, 2021 at 03:46PM

https://ift.tt/39wHYQg

Nevermind at 30: How the Nirvana album shook the world - BBC News

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Nevermind at 30: How the Nirvana album shook the world - BBC News"

Post a Comment