Spinning off companies to exploit products and ideas developed at universities and research institutions can help to address societal challenges and make a real-world impact. Such moves can also be lucrative for scientists who are prepared to take their concepts into industry.

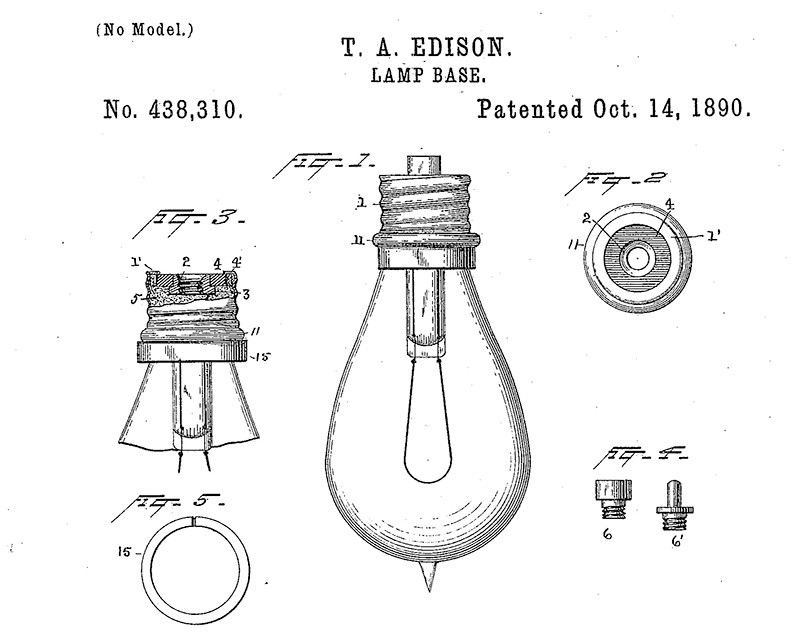

But before a company can start selling a product, it must protect its intellectual property (IP) by patenting the technology that makes it special (see ‘Glossary’).

Nature spoke to five specialists about how to get started (see also ‘Patent search tips’).

JOHN GRAY: Learn what makes your idea patentable

UK and European patent attorney, based in Glasgow, UK.

A fear of a discovery being scooped can create a race between researchers to publish their results as a peer-reviewed paper. But if there is a commercial goal in mind, patent filing should come first: patent laws generally favour whomever is first to file an application that completely discloses a fresh invention.

Researchers should keep in mind three important elements that make an idea patentable.

First, the invention must be new: the same idea can’t have been published before in any form. Publications by the inventors themselves (this would include academic papers as well as talks at scientific conferences or demonstrations to potential customers) can destroy a patent application. Presentations at internal laboratory meetings are OK, but if there are external collaborators present, it is essential for everyone to commit to a project agreement with a non-disclosure clause, to protect any potential patents.

Second, there must be some inventive step of ‘non-obviousness’. This can be hard to define and depends on the context. For example, painting a device a different colour is unlikely to be considered inventive, but a formulation of paint that dries faster, or holds its colour better under radiation, might well be.

Third, the disclosure in a patent must be sufficient for a skilled person to reproduce the invention with only routine effort. For instance, a drug patent usually needs detailed formulations and evidence of effectiveness, and instructions for making any special chemical compounds used.

A patent should cover variations of the product. If the patent describes only one chemical formula, for example, generic drug manufacturers might be able to change the location of a functional group slightly and produce their own product. The patent application should describe likely variations from the outset, with experimental data provided if necessary.

For academic researchers, the main objective of a patent is usually to ensure a start-up company can secure investment for technical development. For start-ups with limited resources, it is helpful to choose the most strategic markets in which to file and maintain patents.

For instance, a start-up that has developed a microchip-production process might only have patents in countries with the infrastructure to manufacture microchips. A start-up firm with a new blood-pressure drug, by contrast, might need to budget for filing patents in dozens of countries — anywhere a generic drug manufacturer can operate. Luckily, international treaties allow a patent application in one country to establish priority for the rest of the world, so that decisions and funding for territorial coverage can follow later.

Online patent databases have improved significantly in recent years, which is good news for researchers. Even free services include powerful machine-translation functions: this means a rough translation of foreign-language patents is just a mouse-click away.

JOHN COLLINS: Do market research and seek out mentors

Commercialization adviser at Innovation Foundry in London, UK.

Many academic researchers will pursue whatever interests them and give priority to experiments. Determining whether their knowledge and innovation can be converted into a patent often comes later, almost in hindsight: it’s a case of a solution looking for a problem.

A better strategy is for researchers to launch a project to tackle a pressing challenge in their field: a problem looking for a solution.

Researchers who are interested in turning their existing research into useful patents should do their homework to find out what’s already been achieved commercially, and whether there are any related patents out there, before spending resources on the patenting process.

Aspiring researcher-entrepreneurs should also find ways to identify potential clients, and read reports and surveys to understand market needs. They should keep in mind the scalability of their idea and monitor news from potential competitors while scouring patent databases.

Mentorship is extremely important for researchers who are hoping to transform their ideas into patents and businesses. I recommend having a few mentors, ideally field specialists and experts in manufacturing and business. I’ve found my mentors through conference meetings, at universities I’ve worked with, and from incubator and accelerator programmes.

As a mentor, one area in which I have supported people is that of early decision-making. In 2014, for example, I worked with a team of six prospective PhD students at Imperial College London who had done well in the International Genetically Modified Machine (iGEM) synthetic-biology competition and wanted to create a start-up from their project.

I weighed up the options and advised them that it would be challenging to juggle between embarking on a PhD and running a start-up. One of the students decided not to pursue his PhD programme and instead launched a start-up with two of the other iGEM team members. He has since gone on to turn their ideas into patents to solve a big challenge in water purification. The start-up has attracted nearly £20 million (US$27 million) of funding over the past 5 years, and the team has grown to 17 people.

BARBARA CHAN: Join a team that shares your entrepreneurship philosophy

Professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Hong Kong.

Researchers are increasingly being asked to consider the broader impact of their work, which includes commercial dimensions. One way to show that is with patents. At my university, I used to sit on grant panels for aspiring researcher-entrepreneurs. The panel members considered patents to be a partial demonstration of the impact of technological innovation and an indication as to whether a start-up is likely to be able to raise external funding.

I often would encourage students to first understand a problem thoroughly, do a literature review on the existing solutions, and think of creative ways to solve that problem. I told them to dare to fail many times at something before finding a useful way for it to be better, cheaper, faster or more accurate. High-impact publications and patents will follow.

If a researcher wants to become an entrepreneur, they should apply to join a lab with a similar philosophy on entrepreneurship. I hold 18 patents and co-founded a start-up that focuses on tissue-engineering technologies, and I’m happy to share my experience. I teach my students to do patent searches and encourage them to attend training workshops, such as those organized by the university’s IP office or organizations such as the Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks Corporation. In this way, they can learn from and network with successful technology entrepreneurs.

A’AN JOHAN WAHYUDI: Solve problems that are close at hand

Senior research scientist at the National Research and Innovation Agency’s Research Centre for Oceanography in Jakarta, Indonesia.

I work in the National Research and Innovation Agency, a newly formed body in Indonesia, and we have a patent office with fewer than 15 staff who help to draft patents. In 2020, I filed a patent for a technique that uses isotopes to calculate how much farmers should feed sea cucumbers — edible marine animals — to optimize their growth. Although sea cucumbers are farmed in several countries, including Australia and Vietnam, I decided to file the patent in Indonesia only. This was a strategic decision, because countries have their own patent-application processes and we do not have the expertise to file patents in global markets.

Many research institutes in developing nations, such as mine, care more about academic publications than patents, and have limited funding dedicated to patent applications. The key to overcoming this obstacle is to be pragmatic and hands-on in one’s approach to invention. My team spoke to sea-cucumber farmers before embarking on our project, for example, to gain an understanding of the challenges they were facing. Although my patent will not solve a global problem such as climate change, I am confident that when it is licensed and deployed, it will add value to local farmers and their businesses.

In my research centre, we regularly communicate with local farmers and businesses in the marine-agriculture industry about their challenges. This system has worked well for us, and could be effective for other researcher-entrepreneurs from developing nations who hope to make a difference with their inventions.

CHRISTINA HEDBERG: Make early contact with a technology-licensing officer

Technology-licensing officer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA.

Licensing officers at universities, such as myself, are valuable partners for scientist-entrepreneurs. We evaluate invention disclosures for patentability and commercial opportunity, and decide whether to file patents on behalf of our institutions. We also negotiate patent-licence agreements between universities and start-ups, and can provide guidance to researchers as to how the process works and what the relevant institutional policies are.

Many of us have decades of experience in industry and we enjoy sharing our expertise and perspective. We can provide introductions to valuable resources, such as strategic investors, pitch competitions and mentoring, which is why it’s important to build a relationship with your licensing officer as early as possible.

When researchers reach out to me with their ideas early, it gives me more time and a better opportunity to understand the science, the potential impact of their work and their entrepreneurship goals. The more we know about the research and where a potential invention fits in, the easier it is to decide whether to file a patent. Working and strategizing with scientists on this is one of my favourite parts of my role as a technology-licensing officer. There have been times when I have advised a researcher that we should file a patent application early, because I understood the science and the commercial context and I thought it would be strategically advantageous to gain that IP as soon as possible.

Although licensing officers can be valuable allies, we also need scientist-entrepreneurs to be cooperative. We need inventors to be available and responsive when we draft patent applications, and to respond to questions from the patent office. Furthermore, inventors can facilitate the process by helping to clarify the commercial application of their technology, which enables us to draft stronger applications. Finally, they should keep us informed of upcoming publications and presentations, so that we have time to file patents ahead of public disclosures.

"how" - Google News

November 15, 2021 at 06:08PM

https://ift.tt/3qGaVTw

How to turn your ideas into patents - Nature.com

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How to turn your ideas into patents - Nature.com"

Post a Comment