But carrying a gun while high on meth dramatically increases your chances of being killed in an encounter with police. While 61 percent of Colorado’s officer-involved shootings over six years ended in death, the combination of meth and guns in the hands of a suspect raises that percentage to almost nine out of 10.

The reason seems clear in reviewing the prosecutors’ investigations. In most of Colorado’s meth and gun cases in the past six years, hypercharged and delusional suspects left officers with little choice but to shoot to protect themselves or the public.

Cases like Bruce Allee, 31, who was killed in Thornton in 2018. He ran from authorities trying to serve him with warrants, before shooting a homeowner in front of his 9-year-old daughter and carjacking a vehicle. U.S. Marshals and federal ATF agents eventually caught up to him and shot him when he jumped out of a car and opened fire on agents. With multiple felonies on his record, he could not legally possess a gun.

Or Austin Uncles, 26, who had a criminal record dating back to when he was a juvenile in Utah and dumped a friend’s body in a park after he died of an overdose. In 2014, a Colorado state trooper saw Uncles with a stolen motorcycle, leading to a foot chase. When Uncles pulled out a gun he couldn’t legally possess and pointed it at an innocent bystander, the trooper lawfully shot him in the back, according to the Denver District Attorney’s office.

Autopsies in both cases found methamphetamine in their bodies, which explained the poor decision making.

“You'd be hard-pressed to find a case where someone was on meth and they did things that were smart,” said Arapahoe District Attorney George Brauchler, whose office has prosecuted scores of methamphetamine cases.

Guns make everything worse.

“What we know about methamphetamine is that when people are using this drug, they're significantly more likely to act out in a violent or hostile manner,” said Rebecca McKetin, associate professor at the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales in Australia. She said heavy meth use leads to paranoia and delusions, and research has found that addicts are six times more likely to behave violently.

That includes even those who don’t have guns.

Bailey Turner, 27, who was convicted of his first felony, for assault, in 2013, attacked a neighbor in an apartment hallway in 2018 while chanting “LSD is great.” He was also on meth.

When an Adams County sheriff’s deputy arrived, he used a Taser on Turner, hitting him directly in the chest with electric probes. They had no effect. When Turner flexed “like the Hulk,” he ran at the deputy with fists flying. Trapped in a confined space and worried that Turner would get his gun away from him, the deputy fired several shots that failed to stop Turner, who kept fighting even as the deputy could see blood spreading across the man’s chest. Turner wrapped his legs around the deputy and tried to pull him to the ground before a 10th bullet fired from close range finally killed him.

Meth is the most commonly seized drug in the Denver metro.

In the city of Denver, possession arrests have increased 176 percent since 2013, according to the latest report to the National Drug Early Warning System.

New Mexico, Oklahoma and Arizona all report a high availability of meth in their states. Each appears with Colorado in the top five of the nation’s states for the rate of law enforcement shootings.

Prosecutors in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which has one of the nation’s highest fatal police shooting rates, have noticed a marked change in the behavior of suspects as meth poured in.

“We started to see a pattern of kind of irrational, aggressive behavior on the part of the people that were being shot or shot at,” said Michael Cox, a special prosecutor in the Bernalillo County District Attorney’s office in Albuquerque. “It didn't make any sense to us.”

Cox dove into the cases and found that meth was implicated in more than 80 percent of police shootings there. Albuquerque has one of the nation’s top rates of fatal police shootings in recent years, and Cox said that’s despite millions of dollars spent on police training and Justice Department intervention.

Part of that results from a proliferation of stolen cars.

“It's almost like a standard, there's a stolen car, a chase, ending in either a wreck or a shootout,” Cox said.

The CPR analysis of officer-involved shootings found that, for individuals who were using meth, stolen vehicles were the second most common call that initiated events ultimately leading to a law enforcement shooting. That’s behind only serving warrants, and tied with checks on a suspicious person — usually someone high on meth and behaving erratically.

“Those are all trends that we're seeing. Unfortunately, meth use is one of the number one things that we're hearing from law enforcement that's pushing our trend of car theft,” said Carole Walker of the Rocky Mountain Insurance Association.

Hart Van Denburg/CPR News

Hart Van Denburg/CPR News

The rise in car thefts has mirrored the rise in officer-involved shootings in Colorado. The number of reported stolen cars rose 72 percent from 2014 to 2018. Pueblo stands out: it ranks 4th in the nation in auto theft per capita. Pueblo also has the most officer-involved shootings per person among large departments in Colorado. The top U.S. cities for auto theft — Albuquerque, Anchorage, Alaska and Bakersfield, California — all rank high in officer-involved shootings and meth availability, according to the federal Drug Enforcement Administration.

Older cars are the usual targets because they’re easier to break into. Thieves often use the car as a place to inject or smoke meth.

There are anecdotal reports of owners getting headaches from their cars after they’ve been recovered. The Salt Lake City Police Department recommends that victims of car theft get the car inspected for meth contamination. One car inspector in Albuquerque said 90 percent of stolen cars he tested had traces of meth in them. Laboratories in Anchorage also reported finding meth in stolen cars.

And the aggressive pursuit of car thieves has contributed to the increasing number of law enforcement shootings.

On an unusually warm February day in 2018, a group of plainclothes deputies and officers followed Manuel Zetina, a 19-year-old suspected car thief, around Colorado Springs as he drove a stolen car. Zetina stopped in the parking lot of a low rise apartment complex on the east side of the city and detectives watched as he smoked what they suspected was methamphetamine before he exited the car.

Several officers from BATTLE (Beat Auto Theft Through Law Enforcement), an auto theft task force funded by fees charged to Colorado auto insurance policies, were in plain clothes and lurking nearby. After Zetina sat on a stoop to talk on his phone, officers decided to make their move.

One grabbed Zetina, but in a matter of seconds, the suspect pulled out a gun and opened fire in several directions.

When the gunfire ended, El Paso Sheriff’s Office Detective Micah Flick was dead, another deputy and a Colorado Springs officer were injured, and an innocent bystander was paralyzed from the chest down. The stolen car that detectives spent an entire day risking their lives to track across the city was a 20-year-old Saturn. It was older than Zetina, who was also killed.

It was one of six auto theft task force operations over six years that ended in officer-involved shootings, according to the CPR analysis. Those shootings by officers injured or killed eight civilians, in addition to the officers and the civilian injured and killed by Zetina in that single operation.

Experts don’t agree on how best to deal with meth-fueled encounters.

Researchers often point to “Crisis Intervention Team” training as one possible solution. Some Colorado agencies were early adopters of CIT training, which includes actors portraying someone in crisis. It’s not a panacea. Westminster Police, for instance, said a higher percentage of their officers have completed CIT training than at nearby departments, yet Westminster has one of the highest rates of officer-involved shootings in the state.

At the academy level, methamphetamine psychosis is an afterthought. Cadets, “don't get an extensive amount of training on it. They get several hours, and they witness it on video,” said David Bruce, Director of the Law Enforcement Academy at Arapahoe Community College.

They spend far more time and effort on alcohol intoxication, Bruce said.

Some experts argue for a radical change in training, something akin to the hands-on way nurses are trained. In this model, officers would gain experience working in mental health facilities, detox facilities, or on suicide hotlines “in an environment in which they're not armed and having to enforce the law,” said Paul Taylor, a certified police trainer and assistant professor at the University of Colorado Denver.

Right now officers are learning how to deal with difficult populations on the job.

“But what mistakes are happening along the way?” asked Taylor.

When Deputy Henry Trujillo confronted Kristian Martinez on an October night in 2017, he used pepper spray and a Taser, but they had no effect.

Trujillo said when Martinez lifted a pitchfork over his head, he pulled out his sidearm and opened fire.

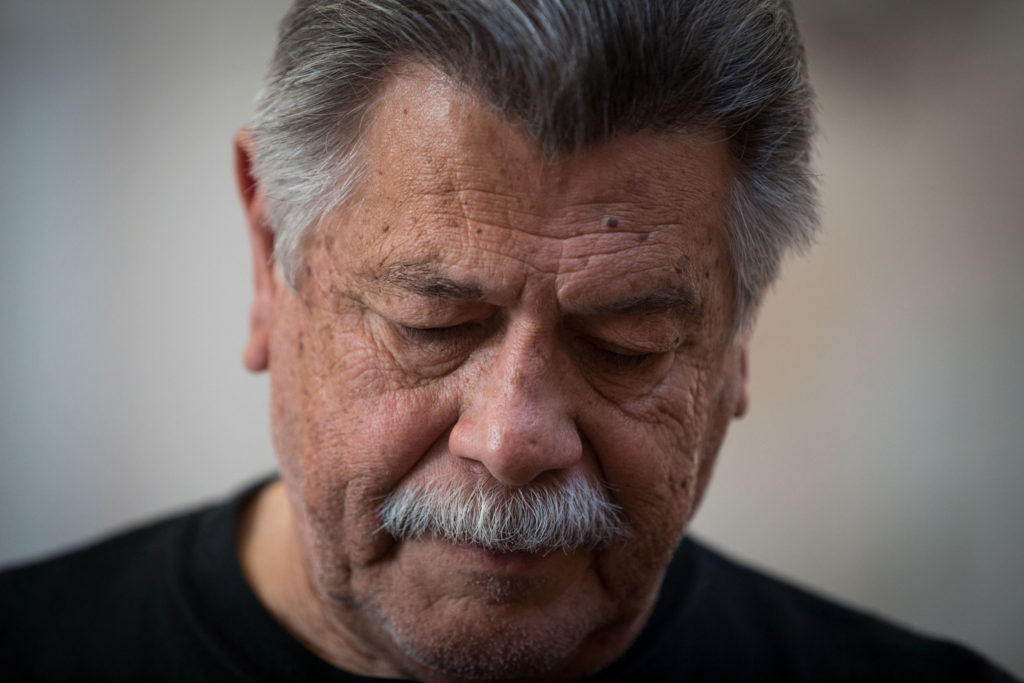

Martinez’s family doesn’t buy the story. Their son, 44, had run-ins with the law, but he would usually run away from, not attack, an officer. The Las Animas County Sheriff’s Office, in the south-central part of the state near the New Mexico border, does not use body cams, and so only two people witnessed it, and one is dead, said Jose Martinez, Kristian’s father.

Hart Van Denburg/CPR News

Hart Van Denburg/CPR News

“My son would still be alive” if the deputy had more training, said Jose, a recently retired attorney who started his career as an investigator for the public defender’s office, had his own practice, and worked 11 years for the Aurora municipal public defender's office.

Time, distance, and cover have long been key concepts in law enforcement training. Case studies routinely fault officers for closing distance too quickly when not necessary, putting themselves in a danger zone where people can be deadly with sharp objects or fists.

It’s not clear why Deputy Trujillo closed on Martinez so quickly. There was a small fire that Martinez had apparently started in a shed in the backyard, but the house was in a rural section of the county far from any populated area. The Las Animas County Sheriff’s Office declined to comment or make the deputy available for an interview, saying they’ll let the investigation of the shooting speak for itself.

“It’s real hard,” Dolores Martinez said through tears. “He was real outgoing.” He made friends easily, but that also meant he made friends with the wrong crowd.

As she sat at the dining room table in her Thornton home recently, Dolores thumbed through pictures of the scene, where her son was killed. They keep a file of the documents they’ve collected on the shooting.

She admitted that Kristian was addicted to methamphetamine, and recalled a time from 2015 when her son had a delusional episode. Thornton police had to hit him with a baton to subdue him. “And on the way to the hospital, he flatlined three times,” she said.

Like her husband, she doesn’t believe the deputy’s account and feels the investigation was biased in his favor, but she agrees with authorities on this: the encounter was sparked by methamphetamine.

“If there is cause or blame, it begins and ends with the fact that there is a proliferation of illegal drugs in the 3rd Judicial District,” wrote District Attorney Henry Solano in declaring the shooting justified.

District attorneys typically confine their investigations to whether a law enforcement officer’s actions in a shooting conform to Colorado law, which allows for the use of deadly force to protect officers or the public.

They rarely step back to ask whether shootings were both justified and necessary. Reflecting on recent cases in his district, Solano pondered whether training could maybe prevent some, even justifiable, shootings.

“I think it's helpful for the officer to have a little more training, both about the response of people, how people respond with methamphetamine, perhaps how to try to use de-escalation techniques, perhaps how to stage and control a scene while there are other officers who might be able to help,” Solano said.

While still distrustful of the sheriff’s department and angry about her son’s death, Dolores Martinez still reserves much of her passion for finding the person who supplied an addict.

“Someone took him meth to his house,” she said. “And that's kinda like one of my goals in my life. I want to find out who took it to him.”

"Many" - Google News

February 05, 2020 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/396BLZ1

Suspects On Meth Are Hard To Take Down With Tasers, So Many End Up Dead In Colorado - Colorado Public Radio

"Many" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2QsfYVa

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Suspects On Meth Are Hard To Take Down With Tasers, So Many End Up Dead In Colorado - Colorado Public Radio"

Post a Comment